Voices

Balancing urgency and patience when the world is burning around us

Looking at the history of our movements for patience also means looking to the future to embrace urgency.

Deana Ayers | 18 Nov 2020

Act with the urgency of tomorrow and also with the patience of 1,000 years.

This quote from Jayesh Bhai is frequently shared by organizers like Mariame Kaba. Both parts of this quote are important for the political moment that we are in. Recognizing the urgency of tomorrow pushes us to take action and try to create the best world that we can as soon as we can. The patience of 1,000 years, however, reminds us that our movement ancestors have been doing this work for generations to get us to the point we are at today.

I fully recognize that balancing these two are more complicated in theory than in practice, but keeping this in mind has been helpful when I try to place my organizing work within the larger movements I’m involved in. Embodying both urgency and patience on a day to day basis has been the only thing keeping me going in these times.

Move at a pace that makes sense

The fires you are panicking about are real. But there are a lot of ways that people and work collapse when folks pretend their hearts and hands can keep up with the pace of state/capitalist violence.

This quote, from organizer and movement educator Kelly Hayes, encapsulates the risks of throwing patience to the wind and chasing urgency with everything we have.

The list of societal wrongs that need to be righted and injustices that must be solved is neverending, and seems to get longer every day. When I start thinking about everything on that list, I get the overwhelming feeling that I need to be spending all of my energy and every second of my day doing something about it. That sense of anxious urgency gets to the best of us, especially those of us who are working with a small crew to try and change our neighborhoods and the world. The drive and passion we have to create a new society as soon as possible is valuable, but it isn’t enough to do what needs to be done. Urgency has to be paired with respect for the capacity of ourselves and our communities.

Forgetting about patience in our activism leads to burnout in activists, but more importantly, it can turn away people that we should be working with and for. Working parents, disabled folks, unhoused people, and other marginalized communities likely aren’t going to be able to spend 5 hours a day attending protests, meetings, and training workshops. Instead of just excluding people with a lower capacity than us, we need to meet them where they are, and create movements and organizations that are accessible to everyone in our communities and neighborhoods.

A helpful phrase to keep in mind when trying to find the pace for your community is “moving at the speed of trust.” The phrase was popularized by Stephen M.R. Covey, but the more applicable definition for organizing comes from Adrienne Maree Brown in her book Emergent Strategy. She describes one of the principles of emergent organizing as moving at the speed of trust, emphasizing the importance of our relationships with those in our community in deciding what pace we can actually work at.

How fast you can move is determined by how much trust you have. And people won’t trust you unless you are vulnerable with them.

The success of our organizing depends on relationships that allow for trust, vulnerability and rest. Ignoring the importance of these aspects leaves behind those with the least time, energy, and capacity. We have to embrace the truth that trust, vulnerability, rest, and care don’t slow down the work, they help us move at a sustainable pace for everyone in our movements.

The only ones here to save us… are us

I want to keep on emphasizing the importance of balancing urgency and patience while we organize. In my own work as an abolitionist and political educator, the last few months have shown me that urgency and patience also dictate when to take action and how fast we need to move. I want to abolish police and prisons as soon as possible, and that means taking actions now around helping to develop the leadership of other organizers and educate them on abolitionist and organizing theory. I found my role, and an organization to do the work in, and that has helped with the balance.

But we don’t all have the luxury of having an organization that we’re already organizing with, and that feeling can lead to a heightened sense of urgency. Wanting to do the work immediately, and leaning into patience, can mean recreating the wheel and spending valuable time and effort doubling the space and effort that others have created. That’s obviously not what we want, but the same can be said about over embracing patience. We can’t spend months or years waiting for someone else to create the movement or campaign or organization that we can plug into. Both sides of this coin waste the valuable time, energy, and passion of ourselves and everyone around us.

There are some guiding questions that can help you do your research on what’s already being organized in your community, and whether or not you should be starting something new.

- Who in your community can you connect with to learn more about movement work, generally and in your neighborhood and city?

- Who’s already doing the work in your community, and do you have the capacity to help them?

- If you want to start a new formation, do you have the resources and/or capacity to make it successful and sustainable?

- Is there someone in your neighborhood or community that you can support in starting something new?

- Have you not taken action because you are nervous about getting started, or because you don’t have the access you need to people, organizations, and resources?

Keeping in mind a balance of patience and urgency is helpful for understanding what to do and when to do it. We can start small, support other people, engage with the work slowly, or whatever works best for us. Just so long as we get started and keep going no matter what.

We aren’t the first or the last to do this work

It’s easy to feel overwhelmed when you’re in a constant political battle with powerful, well-funded, and often violent opposition. No matter how much we mobilize, organize, and throw ourselves into our movements, we don’t have a guarantee that we’ll really and truly win not just the hypothetical battle, but the war.

As a political educator who will never run out of information to learn and teach, and community members to engage with, my work feels never ending. When that feeling of never being done gets overwhelming, I ground myself in the histories of liberatory movement work, and popular education specifically. Organizers and leaders like Ida B. Wells, Assata Shakur, Da’Shaun Harrison, and K Toyin Agbebiyi give me confidence that what I’m doing has an impact, and that I am joining a long lineage of political educators in the Black liberation movement specifically.

The movements we are part of, whether it’s climate justice, prison industrial complex abolition, reproductive justice, or anything else, have a long history that we are building on. Understanding our place in the timeline of our movements can be the key to not burning out from trying to do too much too fast.

My work exists within a history and a present – and therefore a future.

While Travis Alabanza wrote these words in reference to their theater career, the sentiment can also be applied to our movement work. We are part of a lineage of work, and we shouldn’t try to be the first or last to do anything in the work that we’re doing. Often, actions or campaigns that we identify as the first are the most visible, the best known in the age of information, or are an adaptation of past work. This is not to say that it’s less valuable, but instead that all of the work that is being done matters and has an impact, no matter when it happened.

Looking at the history of our movements for patience also means looking to the future to embrace urgency. In my own work, I am hoping to pass the baton by giving my movement descendents my lessons, successes, and advice on how we can all get free.

To do that, I encourage you to ask the following questions when doing organizing or activism:

- What will your words, actions, and work provide for the generations who will come after me?

- Are future generations going to have to clean up after any mistakes you made by moving too fast, too soon?

- Are the movements, campaigns, and organizations you’re a part of sustainable? Will they still be doing good work, or have already succeeded, in 5 to 10 years?

In other words, I ask myself if my movement descendents will be able to create gardens from the seeds that I’ve planted with care and intention, as my movement ancestors have for me.

Moving forward

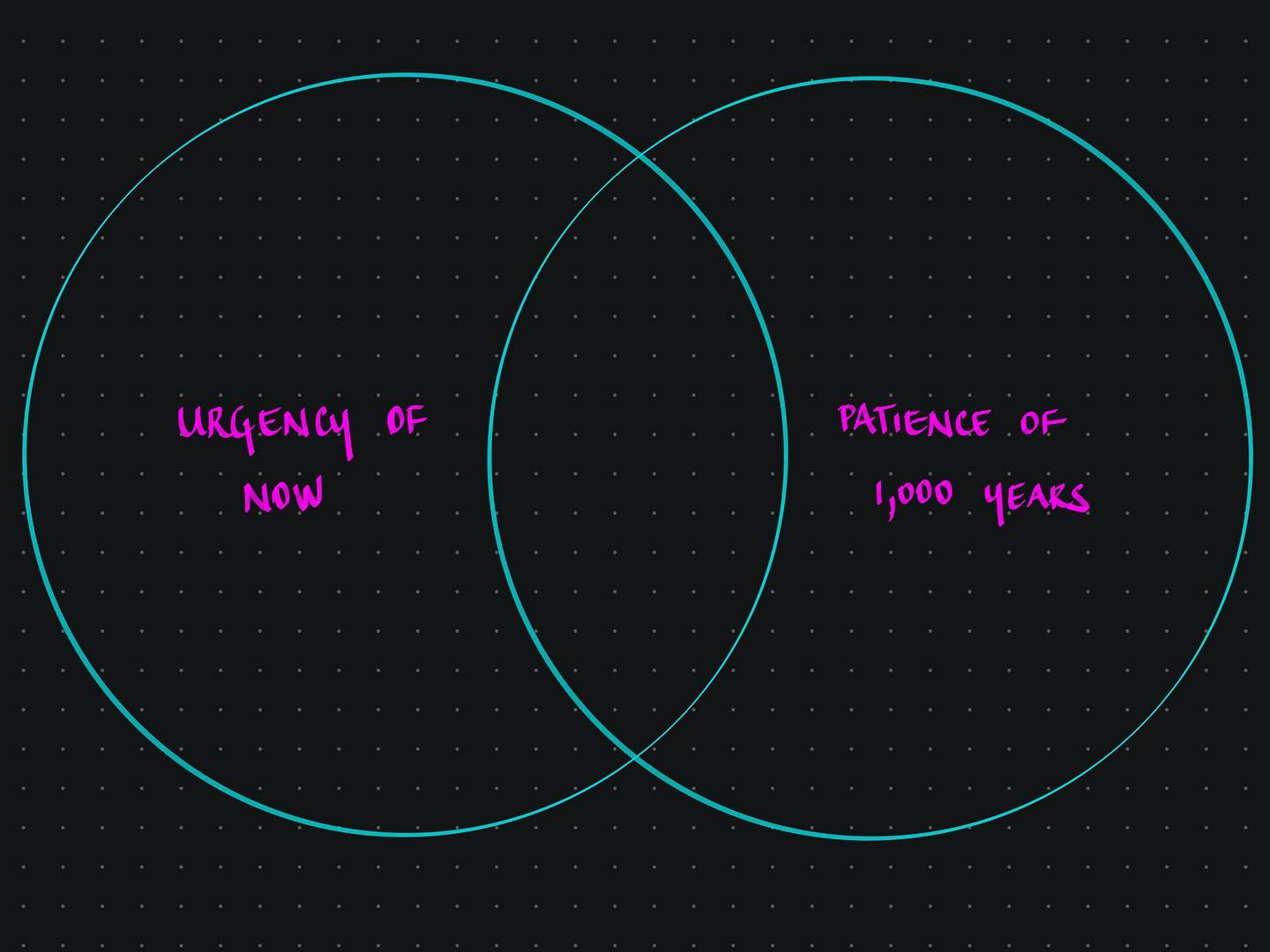

In the center of the venn diagram of urgency and patience lies sustainability. We want to move fast enough that change is created, that we are contributing to the creation of the world we want to see. The urgency of sustainability comes from leaving some legacy of work that others can build upon in the long haul. But we also recognize that sustainability includes being patient with ourselves and recognizing that we will always be bound by our capacity.

As I write this, campaigns, organizations, and movements are grappling with how to keep fighting for justice and liberation while COVID-19 ravages entire cities. In times like these, times of crisis and uncertainty, it is even more important to understand our relationships with urgency and patience. Our relationship with rushing ahead without centering care, and for holding back when important work needs to be done. All of our futures depend on finding a balance between urgency and patience in everything we do.