Voices

Building a Collective Care Response to Trolling

Trolling threatens the safety and wellbeing of our people and undermines the sustainability of our movements - so what can we do?

Act Build Change | 29 Aug 2024

Image credit: Camilo Jimenez.

Trolling is a form of online violence that many organisers and communities have to navigate in the work that they do. This is true of many of the groups we work with at Act Build Change.

As an organising school with a focus on collective care, this is a question that concerns us. We see the many ways that trolling undermines the safety and wellbeing of organisers, and how it can threaten the sustainability of movements. Social media has been a major site of misinformation and an environment where targeted and organised attacks are common.

Within groups the energy to ‘firefight’ against trolling can divert resources and energy away from strategic objectives.

The question of how to navigate trolling and online hate is particularly pertinent in the current context. In the past few weeks we have seen racist, anti-immigrant attacks that have targeted racialised people across the UK and Ireland. Mosques, homes, businesses and hotels housing asylum seekers have been attacked and vandalised. A survey commissioned by Muslim Census, found 92 percent of muslims and ethnic minorities feel “much less safe” as a result of the violent disorder. This violence has not come out of a vacuum and has been enabled by decades of demonising racialised people, immigrants and Muslims especially by the media and politicians.

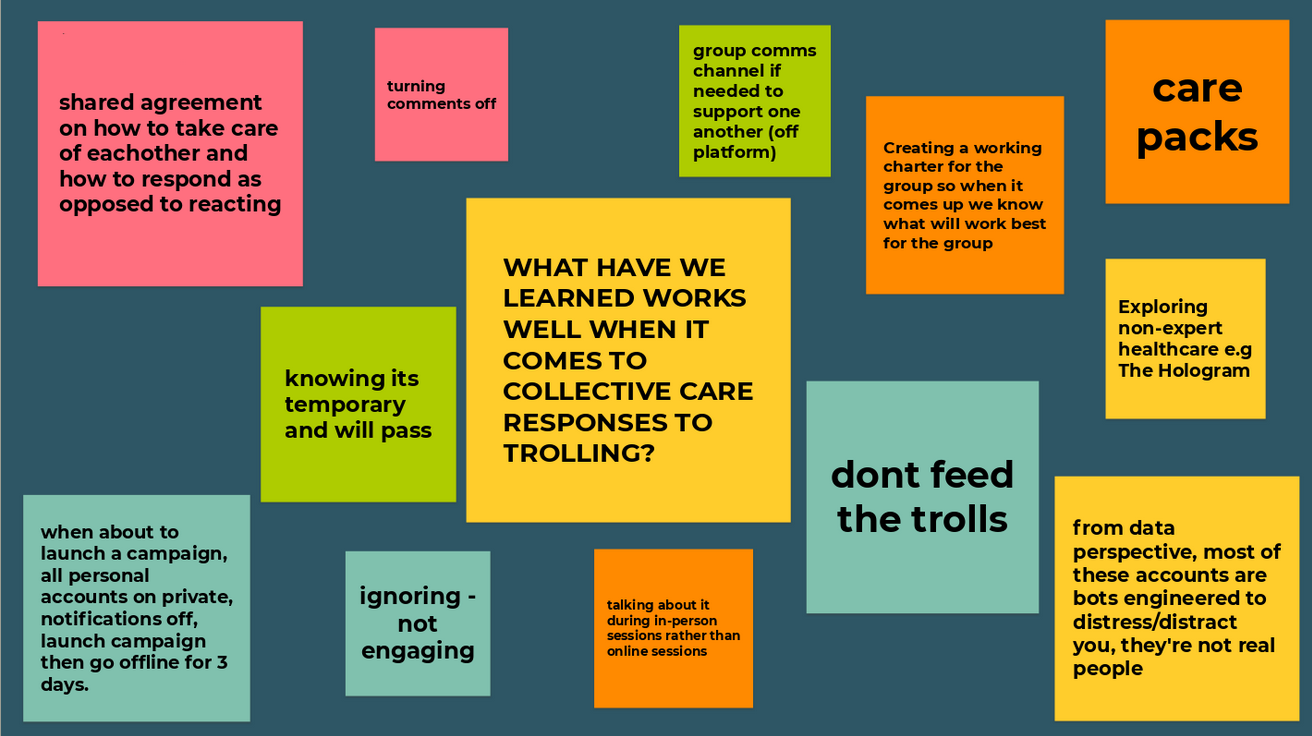

In this blog we share learning from a solidarity space that we ran last year on ‘a collective care response to trolling.’ This space was motivated by challenges raised by groups we work with, many of which are in the migration sector.

We hosted six sessions over the course of a year to provide a space to share solidarity, resources and live practical support, as well as considering what a broad-based strategic response to online hate might look like. Sixteen collectives engaged with us at different points across this work including No More Exclusions, Mermaids UK, the Inclusive Mosque Initiative, Coventry Youth Activists, and Micro Rainbow.

What You Can Do

Trolling becomes more likely as we grow collective power. Organisers we work with have shared that the impacts of trolling on them and those they organise with have included isolation, anxiety, burnout and even withdrawal from organising altogether. Within groups the energy to ‘firefight’ against trolling can divert resources and energy away from strategic objectives.

So, what can we do?

Three key principles emerged from our discussions:

- Prepare and plan

- Provide dedicated peer support and care

- Build a broad-based response

Prepare and plan

Trolling can trap people in a defensive place and thrives off reaction. The importance of forward-planning was emphasised as an effective strategy across our conversations.

As one participant shared, “one of the things that is often missing is a robust plan for when things go wrong, especially regarding marginalised community members most at risk.”

Effective planning strategies could include:

- Ensuring staff are adequately briefed and aware of the risks of public association with particular campaigns or events.

- Robust advice is given on protecting their identity and staying safe online. This includes ensuring that passwords have two-factor authentication. One participant shared that their organisational strategy is “when about to launch a campaign all personal accounts on private, notifications off, launch campaign then go offline for three days.”

- Creating space to collectively strategise and for all individuals who are involved to have the opportunity to feed into this. Ensuring that debriefs take place and that learning is shared and actioned.

- A calendar view that anticipates potential moments of high risk where additional support, capacity or resource can be helpful.

- A key point on online safety with trolls is a reminder that it is most often counterproductive to reply to online trolls. It is best to block and ignore. While some reported more success with the tactic of appealing to prominent advertisers to engage with social media platforms on their behalf, beyond this any direct response to trolling often throws fuel on the fire.

Provide dedicated peer support and care

It’s vital to put robust safeguarding and support structures in place in advance to ensure people have access to support when it is required. This is a collective responsibility and should not be left to the individuals most or most likely to be affected.

Helpful practice includes:

- Creating dedicated spaces for peer support. Our sessions showed us that the value of spaces to share experiences, decompress or to name fears and concerns cannot be underestimated. Participants expressed feeling ‘immensely comforted’ and ‘less alone’ by having the opportunity to be in this space.

- Consideration of vicarious trauma, both for the collective as a whole and the individuals within it. Online hate will affect everyone differently based on their experiences and identities. Space to contain a diversity of experiences in relation to trolling is fundamental to shaping more nuanced care support.

- Provision of aftercare for those who have experienced threats and trolling. This should include asking affected individuals what support they need and continue checking in after an incident has occurred.

- Participants shared that direct offers of support after incidents of online hate was also valued as it was not always clear to identify what they needed. This could include telling staff to take time off work, changing elements of their work for a period of time or offering supervision support.

- If you are working with freelancers or partner organisations ensuring their time is adequately remunerated for the time that dealing with unanticipated trolling or press fallout can take.

- Sending messages of solidarity. As one participant shared “sending messages of solidarity (even if just privately) to groups who are facing trolling can give a valuable morale boost and help people feel less alone. I felt that when I had been targeted myself.”

- Creating dedicated collective spaces to organise and share knowledge on strategies around online hate can be supportive. As one participant shared: “While there are some great resources on trolling out there, it’s useful to have space to talk through this collectively, and share experiences and advice.” Another participant shared: “Resources and ideas to collaborate were really creative and inspiring - feels like a problem we can tackle better collectively even if we don't have all the answers right now!”

Build a broad-based response

A key takeaway from our solidarity space was agreement on the need for a more broad-based response to online hate, building solidarity at a movement-wide level. Within this, there was the question of what role larger organisations with more resources and access to legal support could play.

Many participants shared how social media reporting systems are often ineffective at best. As one participant shared “systems do not work as there is so much prejudice embedded in the algorithms.” Another participant shared that “reporting is re-harming and most of the times ignored.”

In the absence of effective reporting mechanisms - those affected spoke to the need for groups doing social justice work to look out for one another and provide ‘safety in numbers’ for those working on the sharpest edges or who are more likely to be scapegoated.

The reality is that while particular communities or causes will receive mainstream support, sympathy and backing against trolls, others will be considered ‘ or ‘too complicated’ to comment on. It will often be politically or strategically convenient to affirm demonisation, or to remain silent. We saw examples of this in our spaces when it came to Pro-Palestine activism, young people excluded from education, or those organising around the rights of trans young people.

Reflective questions

- What are your current strategies for online violence? What is working well and where are there gaps?

- What are the ways that you can support those in the most visible or front-facing roles?

- If your organisation relies on working with grassroot collectives, how are you practically showing up for them in times of online hate?

- How can you ensure that the burden of ‘dealing with’ trolling does not fall on those directly affected?

- What is one way you can improve the online security of the group that you work with?

- Who are three organisational allies you can reach out to for support in the form of ‘safety in numbers’ when experiencing trolling?

- What process can you have in place to safeguard staff ahead of planning for potential trolling?