Voices

Joy for radicals

How to thrive in resistance during toxic times.

Jean-Michel Knutsen | 14 Jan 2020

This post was translated into English by Dominique Knutsen.

- Have you ever decided not to publish something on social media to avoid confrontation by activists?

- Have you resigned from an organisation because a small number of people imposed their ideas on others and it was too difficult to stay?

- Have you been lectured by people who say you don’t know anything about social change, your actions are useless, and you aren’t giving enough time to the cause?

If you answer yes to any one of these questions, it is likely you are encountering rigid radicalism. This is a pervasive phenomenon affecting civil society in many different ways and remains difficult to define and overcome.

The purpose of this article is twofold. Firstly, to offer a better understanding of rigid radicalism and secondly, to shed light on joyful militancy, a form of engagement free of such radicalism.

What is rigid radicalism?

Although I have experienced rigid radicalism myself several times, I was only able to put a word on it thanks to the book Joyful Militancy, written by two Canadian anarchists, Carla Bergman and Nick Montgomery.

They define rigid radicalism as:

In some milieus, the currency of good politics is a stated (or demonstrated) willingness for direct action, riots, property destruction, and clashes with police. In others, it is the capacity for anti-oppressive analysis, avoidance of oppressive statements, and the calling out of those who make them. […] In some it is the capacity to have participated in a lot of projects…In every case, there is a tendency for one milieu to dismiss the commitments and values of the others and to expose their inadequacies.

I felt relief when I read these words for the first time. I was not the only one to feel this way! Not only that, but Bergman and Montgomery found the courage to put words to this phenomenon in an attempt to understand it better.

The challenges of the newcomer

When a person attempts to integrate into a group whose culture is rigid and implicit, the newcomer faces a dilemma: either they are placed under the authority of more experienced members of the group (which can lead to abuses of authority or even humiliation), or they can reject the status of “newcomer”, preventing them from integrating into the group.

The newcomer is immediately placed in a position of debt: owing dedication, self-sacrifice, and correct analysis that must be continuously proved. Whether it is the performance of anti-oppressive language, revolutionary fervour…those unfamiliar with the expectations…are doomed from the start unless they “catch up” and conform. In subtle and overt ways, they will be attacked, mocked, and excluded for getting it wrong, even though these people are often the ones that “good politics” is supposed to support.

This is key to understanding and integrating several seemingly unrelated problems in the militant world. Indeed, if a group develops a rigid culture and uses a set scale of values to judge everyone’s behaviour, it creates an oppressive atmosphere that spares absolutely nobody.

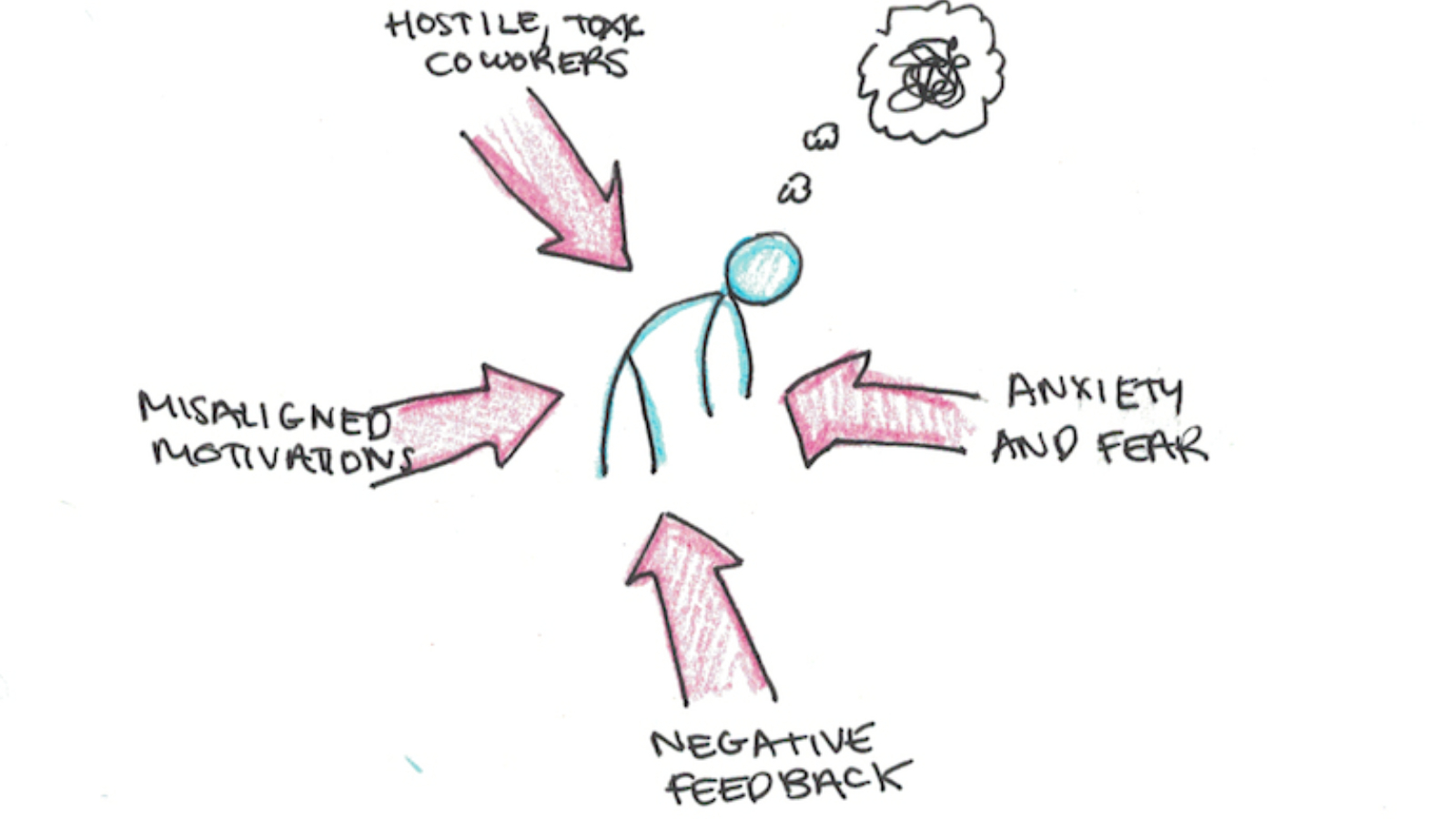

From paranoid evaluation to self-inflicted burnouts

Rigid radicalism creates groups in which each behaviour, or even each word, is measured and judged according to the group’s excessive expectations. Newcomers are automatically scrutinised, and the slightest error is used as an excuse for organising a session of “radical-splaining”.

More experienced group members also face difficulties, as they are constantly required to prove they deserve to keep their place in the group. They are met with comments like, “You’ve missed two meetings in a row. Can we still rely on you?” or “What’s this post you shared on Facebook? Are we still on the same page?”.

A culture based on rigid radicalism is an “all-or-nothing” system. A group member can either sacrifice themselves for the cause and meet all of its demands or provoke the wrath of others. As Bergman and Montgomery, this group culture necessarily leads to burn-out:

rigid radicalism induces a sense of duty and obligation everywhere, there is a constant sense that one is never doing enough… “[B]urnout” in radical spaces is not just about being worn out by hard work; it is often code for being wounded… What depletes us is not just long hours, but the tendencies of shame, anxiety, mistrust, competition, and perfectionism… [T]hese tendencies stifle joy: they prevent the capacity for collective creativity, experimentation, and transformation.

Rigid radicalism is a form a nihilism

Rigid radicalism stems from our perception of the world as useless, damaged and full of errors and weaknesses.

We prefer to criticise things that don’t work rather than focusing on things that do. This does not mean that criticism is always bad or that we should not worry about social or climate emergencies. But such criticism can become rigid if expressed within a negative perspective where there is no hope and where we constantly dwell on flawed and incomplete things.

This is why they state that the existential origin of rigid radicalism is nihilism. Inspired by Nietzsche, they explain that radicals with an exceedingly critical attitude towards the world often end up rejecting the world as it is and prefer to focus on a world that is no longer here (or does not exist yet).

This is, therefore, the fundamental origin of rigid radicalism in the militant world: we focus so much on our ideas, our procedures and our programs that we become slaves to them.

How, then, can we defend our ideas, our methods and our programs without falling into rigid radicalism? Is there a fair balance between our principles and excessive rigidity?

According to Bergman and Montgomery, defining rigid radicalism is not an end in itself.

it is a mere first step in understanding why militants lack joy. The next step is rediscovering the joy of working together.

Joy is an expression of power

Baruch Spinoza, a Dutch philosopher, believes power is a profound and personal thing: our power (potential in Latin) is our ability to assert ourselves in the world.

From Spinoza, joy means an increase in a body’s capacity to affect and be affected. It means becoming capable of feeling or doing something new. This increase in capacity is a process of transformation, and it might feel scary, painful, and exhilarating, but it will always be more than just the emotions one feels about it. It is the growth of shared power to do, feel, and think more.

In other words, feeling joyful means becoming aware that our power is increasing.

Too abstract? Then, before you read any further, here is an exercise for you.

Task

Remembering Joy

Try to remember the last time you felt deep joy, a real moment of bliss where everything felt lighter, simpler and more obvious.

Have you found that moment? Do you remember it in detail?

Now test Spinoza’s definition. When you felt such joy, did you also feel other kinds of emotions? For instance, did you feel in harmony with yourself, others, and the rest of the world? Did you feel more in control of things? Did things feel simpler to you?

If so, this means that the joy you experienced reflected an increase in your ability to assert yourself in the world – in other words: an increase in your power.

With a little help from my friends

Spinoza’s definition of joy can be used to redefine militancy. Feeling attuned to others emotionally immediately contributes to increasing everyone’s power. Connecting and collaborating enables us to handle heavier loads and accomplish more ambitious projects.

In this context, joy is a political emotion because it is reached by several people at once in a feeling of harmony that requires connecting with others, like when a musician plays in an orchestra or when an activist joins a demonstration.

Loving relationships can be what allow us to face the things we fear about ourselves. They can help undo the ways that we have internalized notions that we are not good enough, not worthy of love, or that we have to put up with things that deplete us and those we care about. […] They can be what make us dangerous and capable of fighting in new ways.

This idea of public friendship can help us overcome rigid radicalism and develop joyful militancy because that kind of friendship reflects the power that citizens can build together if they make an effort to discover what they have in common.

Ultimately, what Bergman and Montgomery teach us is that organising is not about being radical; it is about building joyful relationships.

This post was translated into English by Dominique Knutsen.