Voices

Mumshie Survivor – Storytelling for Social Change Chapter I

Yvette shares the story of her call to leadership and her vision for a movement led by and for migrant women.

The Southeast and East Asian Women’s Association (SEEAWA) | 25 Jul 2024

Earlier this year, Act Build Change partnered with the Southeast and East Asian Women’s Association (SEEAWA), a grassroots organisation led by and working with women who trace their heritage to Southeast and East Asia. Its Let Us Lead the Change Training Programme aims to develop the knowledge and confidence of members who have survived domestic abuse and trafficking to become advocates for change.

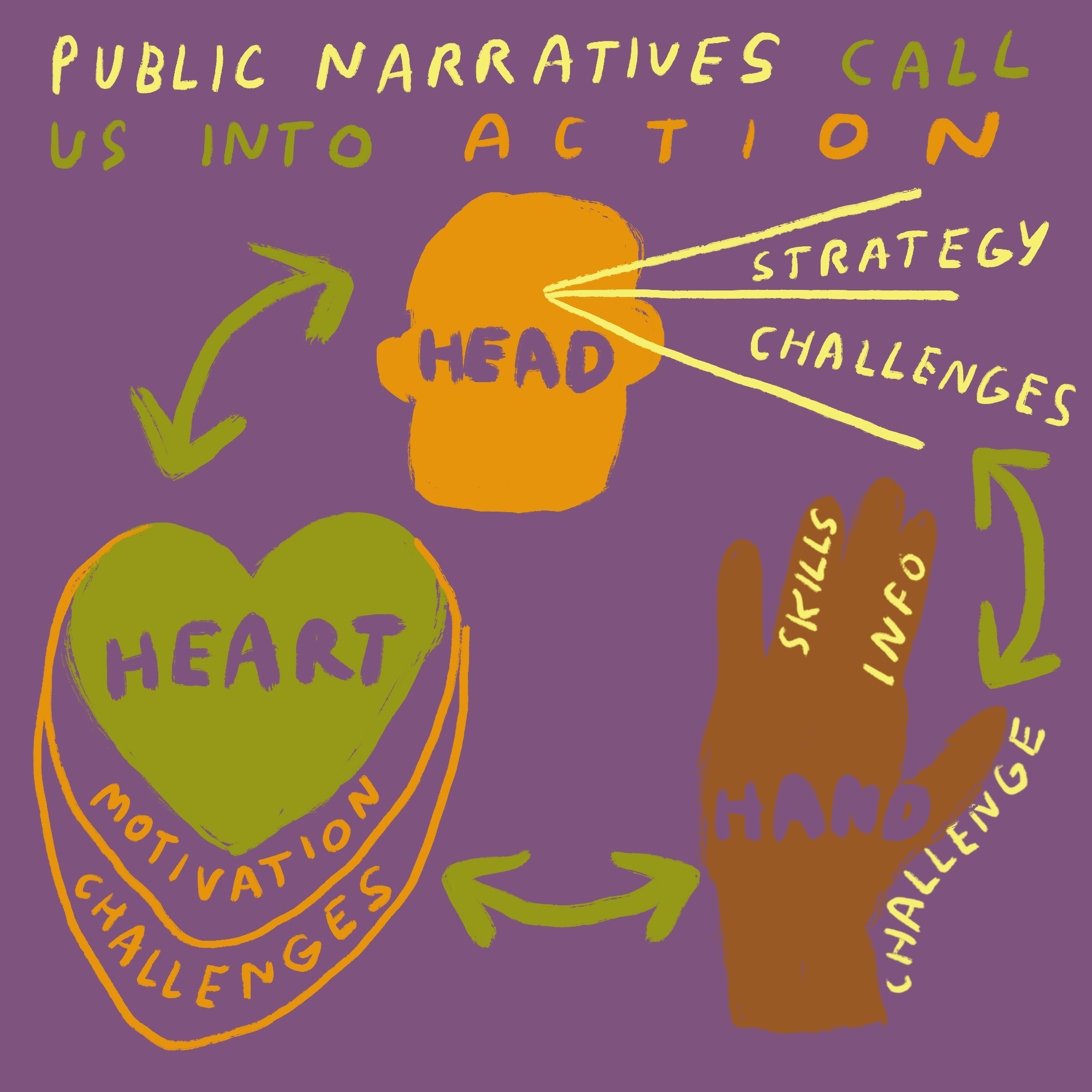

As part of the programme, Act Build Change delivered transformative organising workshops supporting the women of SEEAWA to begin an exploration of what it would take to organise for change. Our sessions were co-produced based on the needs of the group. They explored boundaries in transformative work, how we build power with communities, and using public narrative to campaign for change.

Here one of the participants, Yvette, shares in her first published article the powerful story of her call to leadership and her vision for the movement she now is determined to build.

I came to the UK in 2008 because I was invited by a recruitment agency to be a management trainee at a hotel. I have relatives back in the Philippines who are sick and can’t work. They rely on me to survive. I had worked abroad before and this seemed like a good opportunity to build a better life for my family.

When I arrived, the only job waiting for me was as a waitress and this proved to be the least of my worries. As the only Asian migrant worker at the hotel, I faced discrimination on a daily basis and eventually when my colleague failed to renew my work visa it felt like a punishment. I was told I had to leave the country but if I did that, then I would have no way to keep supporting my family and pay off the debt I owed to the agency that brought me here in the first place.

I found another job in London but I couldn’t afford to sleep anywhere except the street. I saved all my money to send home, pay my debts and eat at McDonalds, where I’d wash my face, brush my teeth and change in the mornings before work. I am lucky that I was able to stay safe until a Filipino family took me in.

Eventually, I met someone who I thought I’d build a home and family with, but the relationship became abusive. In my experience it is not uncommon for Southeast Asian women to endure sexual, emotional and financial abuse without recognising it as abuse because we are taught that abuse is only kicking and punching.

It’s hard for anyone to leave an abuser - and it’s doubly hard when you are undocumented. Your abuser holds your whole life in their hands and can destroy it in an instant if they choose to. We applied for a partner visa to legalise my life in this country and bring an end to the constant fear of deportation. The day he failed to show up in court for it was one of the worst days of my life.

This is what it means to be an undocumented survivor living in the UK’s Hostile Environment. You live in a world of fear and impossible choices and you have no one to turn to.

Soon after things ended, I found myself in yet another abusive relationship. I had already survived one traumatic sexual assault in my past and I was looking for somewhere safe but I didn’t really know what safety felt like. What I do know, is that when my son was born and I became responsible for creating his safety, my world changed forever. I knew now what love and safety meant because it was what I wanted to give to him.

By the time Covid hit, I was out of that relationship but I was heartbroken and traumatised. And when I lost my job during lockdown, I had no way to pay rent and no recourse to public funds. My child and I were facing homelessness.

Whenever I tried to reach out to the council, I was treated with such contempt. I was getting regular episodes of chest pain and breathlessness but I was afraid to go to the GP in case I was deported or my child taken away by social services. This is what it means to be an undocumented survivor living in the UK’s Hostile Environment. You live in a world of fear and impossible choices and you have no one to turn to.

My panic attacks got worse and worse until one day I was rushed into A&E and hospitalised because I couldn’t breathe. I was shocked when the doctors told me I was physically fine. I remember lying in that bed thinking that if my anxiety and depression could land me in hospital, unable to care for my child, I had to make a change.

I had a really hard time trusting anyone but I decided to follow up on a referral I was given to Kanlungan, which supports and empowers Filipino, East and Southeast Asian migrants in the UK. It was my hope for my son’s future that gave me the courage to reach out. This time, finally, someone came through for us.

The counselling I received through Kanlungan changed my life by helping me understand that what I was going through was a normal consequence of the abuse, exploitation and isolation I had endured. The more I understood my flashbacks and panic attacks, the more resilient I became and with the support of this community I was able to be a better mother to my child.

When my son was born and I became responsible for creating his safety, my world changed forever. I knew now what love and safety meant because it was what I wanted to give to him.

I am someone who believes blessings should be shared, so as soon as I was on my feet again I wanted to volunteer, to give something back. Soon, I was developing and leading projects to help fellow survivors from my community find safe space for recovery and re-bonding with their children.

Right now, I’m running three projects for Kanlungan’s Mumshie’s group: one does this through interactive arts, with crafts for the older children and messy play for the little ones; one is reintroducing traditional Filipino games to our UK-born children to preserve the joy in our cultural heritage; and the third is a cooking workshop.

We get together and share our knowledge of cooking and baking, meals and of course dessert, which is very important in the Philippines! Then, we have a tradition that we call ‘kamayan’ where we lay down everything we’ve prepared on a table and sit in a circle eating by hand. These are all precious practices in our culture which bring us together and that we want to preserve.

Through sharing and listening to each other we have become stronger, found inspiration and developed the confidence we need to lead our community forwards.

Having been involved in the development of SEEAWA from our earliest days, I am now also very proud to have been appointed as a trustee. As women from neighbouring regions, we share not only a common culture, but common threats, from gender-based violence, insecure housing, trafficking, economic exploitation and the immigration system - all made worse by the Hostile Environment. To meet these big challenges we need a big community and ultimately, a broad movement for change.

SEEAWA's Let Us Lead the Change Training Programme helped us understand how we can begin building this movement. Our sessions brought us together as survivors ready to speak out and act together. Through sharing and listening to each other we have become stronger, found inspiration and developed the confidence we need to lead our community forwards.

You can support our work at SEEAWA by donating or volunteering.