Voices

The Tyranny of Structurelessness

What do the French “Yellow Vests”, the activists of “Occupy” and the Spanish “Indignados” have in common? No one is in charge.

Jean-Michel Knutsen | 18 Feb 2019

This post was translated into English by Dominique Knutsen.

What do the French “Yellow Vests”, the activists of “Occupy”, and the Spanish “Indignados” have in common?

They all are reluctant to organise themselves formally. Why? Because they feel a legal structure goes against one of their core values: equality. Structures separate people and give them different statuses: Why would anyone build a hierarchy in their social movement? By rejecting those structures, activists create spaces where everyone is equally welcomed and allowed to participate however they like.

This radical choice has a price: when everyone is equal, everyone is equally accountable, which means no one is in charge. It relates to one of the most difficult problems an organiser has to face: how to structure a group of equals.

So when some French “Yellow Vests” wish to coordinate their efforts, they face some burning questions: who are you representing? Why do you think you can make decisions? What is your agenda?

In that context, reading Jo Freeman’s “The Tyranny of Structurelessness” is still relevant today.

Who is Jo Freeman?

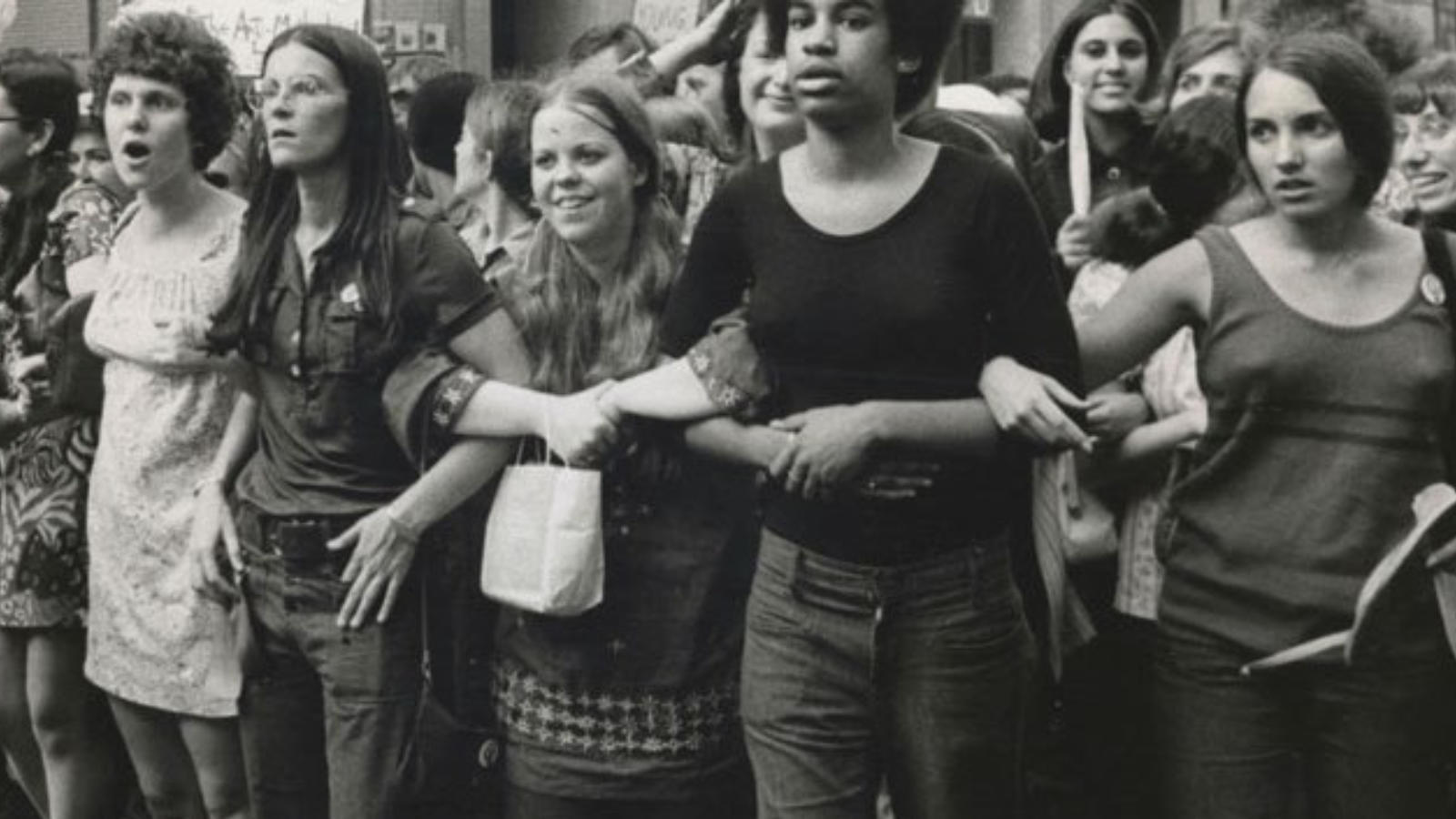

Jo Freeman (born 1945) is an American organiser and intellectual whose militant commitment and academic work are recognised worldwide. At the beginning of the 1960s, she studied at Berkeley and joined the civil rights movement. At that time, she experienced the sexism that prevailed in academia and so-called “progressive” movements.

During a famous conference bringing together the radical left-wing leaders of the United States in August 1967, Jo Freeman was in charge of a workshop on women’s liberation. During this workshop, the participants devised several ambitious demands to share with the other groups. However, when they attempted to contribute, the conference organiser stopped them from addressing the audience. One looked down at them and said: “Cool down, little girl. We have more important things to talk about than women’s problems.”

This event triggered Freeman’s feminist engagement. A few days later, she invited the workshop participants to a meeting in her flat in Chicago. Their conversations led to the formation of the Chicago Women’s Liberation Group. Their monthly newsletter (Voice of the Women’s Liberation Movement) was shared nationwide and contributed to creating the Women’s Liberation Movement.

Deciding to dedicate her work to the women’s liberation movement, Freeman was invited to participate in a Southern Female Rights Union workshop in Mississippi in May 1970. Instead of focusing on her usual topics (such as academic sexism, feminist awareness and women’s visibility in politics), she critically analysed how feminist groups were organised at the time.

Is it possible to organise a structureless group?

At the time, one of the main features of the American Women’s Liberation Movement was its strong opposition to the idea of hierarchy.

Feminists considered vertical (top-down) leadership in activist groups oppressive and dangerous. This is why the thousands of feminist groups at the time claimed to be structureless. There was no leader; each voice would be heard and valued, and all responsibilities would be redistributed regularly, with an agreement reached after every decision.

Structurelessness was especially efficient within awareness-raising groups, where it helped to create a safe place where all participants could voice their concerns.

Unfortunately, it is not as effective when groups need to make operational decisions – especially under time pressure. When people in the movement disagree, personal power struggles often shatter participants’ initial desires to reach a consensus or to listen to each other carefully. While their initial goal was to free themselves from domineering structures, feminist groups had created spaces in which structurelessness limited their actions instead of giving them more freedom.

As a direct witness of structurelessness and the frustration it generated, Freeman devoted part of her research to the sociology of organisation in feminist groups. Her speech of May 1970, entitled “The Tyranny of Structurelessness”, was written in this context.

There is no such thing as a structureless group

At any small group meeting, anyone with a sharp eye and an acute ear can tell who is influencing whom. The members of a friendship group will relate more to each other than to other people. They listen more attentively, and interrupt less; they repeat each other’s points and give in amiably; they tend to ignore or grapple with the “outsiders” whose approval is not necessary for making a decision.

In her article, Freeman explains that an activist group involves people with multiple identities and life histories. Some have more experience, knowledge or ideas, sometimes encouraging them to impose themselves on others. Similarly, some people have a strong personality, like to be in charge, or simply tend to take over the conversation or be quieter and won’t speak out so readily. In this context, the group always has an information structure shaped by its members’ personality and posture.

Some will adapt to a central position and behave as leaders; others will recognise this leadership and become followers; still, others will contest this leadership and become outsiders. Who has never encountered this kind of situation?

All of us involved in community organising will experience these kinds of dynamics playing out in our work. This cannot be avoided in human groups. People are so different from each other that it is impossible to reach a situation where everyone would be equal.

When groups decide not to have a structure, they are referring to their visible hierarchy. They have a structureless group because they have no official leaders, no formal hierarchy or pre-established rules. This doesn’t mean the group has no unofficial leaders, informal hierarchy, or implied rules. In other words, an invisible structure has been created, and invisible structures mask domination mechanisms.

The tyranny

“A laissez faire” group is about as realistic as a “laissez faire” society; the idea becomes a smokescreen for the strong or the lucky to establish unquestioned hegemony over others.

A group without apparent structure leaves the door open to unelected, informal leaders. Because such leadership is not acknowledged, it cannot be held accountable. This is problematic because leaders can behave badly. If there is a formal democratic structure, groups can go against the behaviour of dominant leaders. However, if the group pushes for structurelessness, where no one has more say than the other, we have no mechanism for acknowledging these dynamics. And the dominant leader can exercise their power over the group without limits or boundaries.

Sometimes, a group adopts a few simple rules, such as organising frequent debates or organising a vote when an important decision needs to be made. But more is needed. Who chooses the topics to be debated? How are votes prepared?

Power hides within all of the micro-decisions made before and after meetings. And, once again, when there is no democratic structure, this power is within the hands of informal, unaccountable leaders.

Where do we go from here?

Once the movement no longer clings tenaciously to the ideology of “structurelessness,” it is free to develop those forms of organization best suited to its healthy functioning. This does not mean that we should go to the other extreme and blindly imitate the traditional forms of organization. But neither should we blindly reject them all.

Jo Freeman does not just criticise structurelessness in activist groups. She also suggests several solutions.

1. Distribute authority among as many people as possible

Distribution of authority among as many people as is reasonably possible. This prevents monopoly of power and requires those in positions of authority to consult with many others in the process of exercising it. It also gives many people the opportunity to have responsibility for specific tasks and thereby to learn different skills.

This relates to the work of Ella Baker, who, without, would not have had a civil rights movement. Ella believed that rather than creating leaderless movements, we must create leaderful ones where everyone has moments to lead, develop, be accountable, and share responsibility.

2. Rotate tasks frequently to ensure they are no one’s “property”

Rotation of tasks among individuals. Responsibilities which are held too long by one person, formally or informally, come to be seen as that person’s “property” and are not easily relinquished or controlled by the group. Conversely, if tasks are rotated too frequently the individual does not have time to learn her job well and acquire the sense of satisfaction of doing a good job.

3. Share information frequently because information is power

Diffusion of information to everyone as frequently as possible. Information is power. Access to information enhances one’s power. When an informal network spreads new ideas and information among themselves outside the group, they are already engaged in the process of forming an opinion — without the group participating. The more one knows about how things work and what is happening, the more politically effective one can be.

Each solution requires a genuine commitment from the group members. Sharing power, equal treatment, and information transparency cannot be dictated. It is necessary to formally acknowledge them as governance principles and find a way to respect them. Resorting to apparent structurelessness means neglecting the required effort to build democracy in social movements.

The tyranny of structurelessness is why so many of our ambitious movements today still fail to make it past the mobilising stage of outrage and advocacy – to create real and lasting impact. It is why Jo’s paper is as relevant now as it was almost 50 years ago. Are we ready to listen?

This post was translated into English by Dominique Knutsen.