Voices

Why do we learn so little about Ella Baker?

The answers are wrapped up in sexism, leadership and ego.

Stephanie Wong | 9 Dec 2017

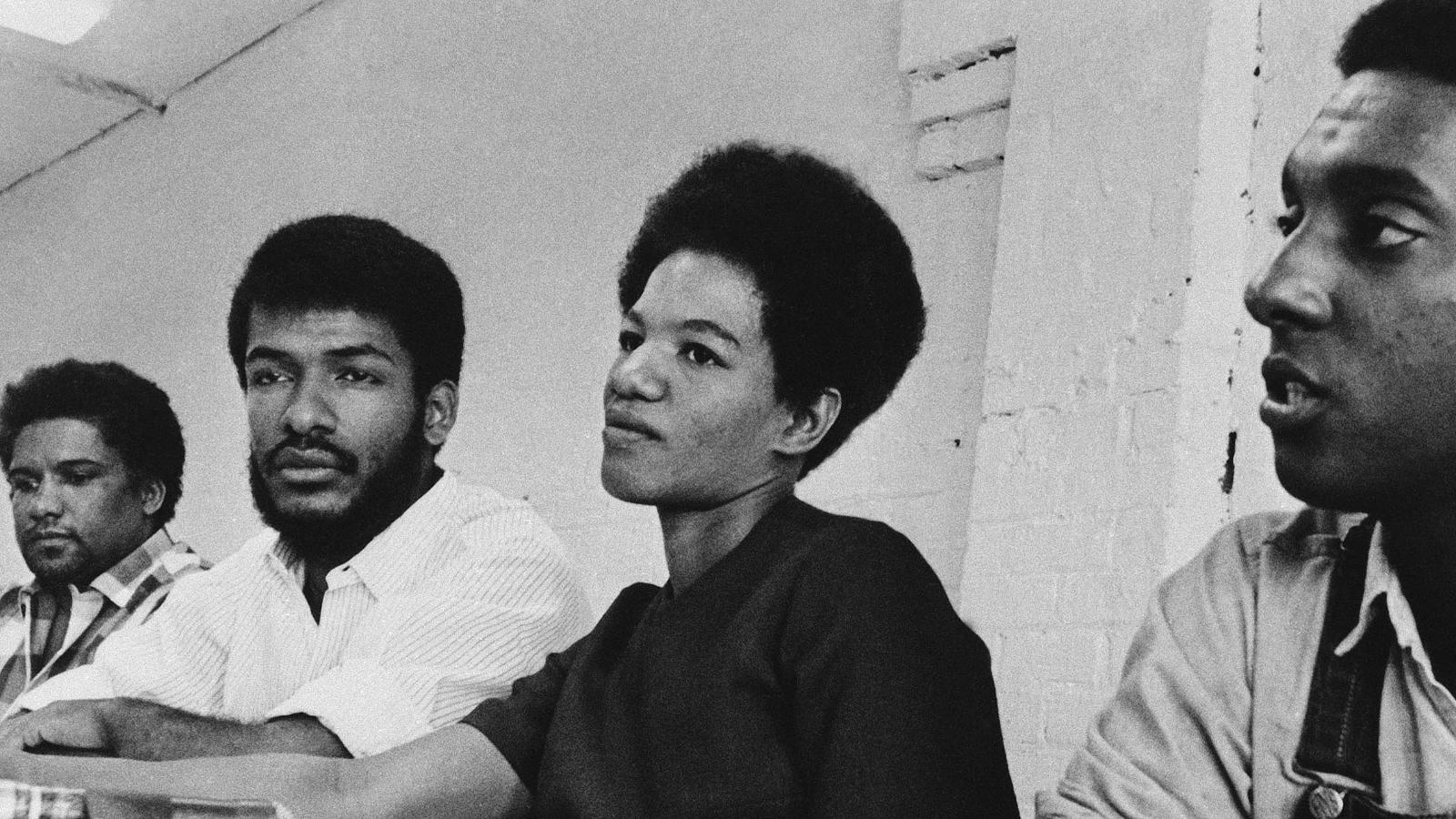

Ella Baker. Image credit: SNCC Digital Gateway.

Without Ella Baker, there was no Martin Luther King Jr.

Without Ella Baker, we may have never known Diane Nash, Stokely Carmichael and Rosa Parks.

Without Ella Baker, there may have never been a civil rights movement, or at least not the one we celebrate.

So why do we know so little about Ella Baker?

The beginning

I came out of a family background that involved itself with people.

Ella Josephine Baker was born in Norfolk, Virginia, on 13 December 1903. Influenced by her grandmother’s stories of life under slavery, Ella started her activism as a young child. Her grandmother’s courage in the face of racism would inspire Ella throughout her life to organise.

Building the civil rights movement

Give light and people will find the way.

For over five decades, Ella organised with the most famous civil rights leaders of the time: W. E. B. Du Bois, Thurgood Marshall, A. Philip Randolph, and Martin Luther King Jr (MLK). Ella also mentored up-and-coming activists like Diane Nash, Stokely Carmichael, Rosa Parks and Bob Moses.

Ella was gifted at building organisations, including the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People (NAACP), MLK Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). Without Ella, leaders like MLK would never have secured the people’s support they needed to ensure their leadership.

Sexism in the Civil Rights Movement

I had known, number one, that there would never be any role for me in the leadership capacity with SCLC. Why? First, Im a woman. Also, Im not a minister.

Ella saw herself as equal to the men she worked with. She called out the sexism within the civil rights movement’s leadership and argued for change. Ella believed sexism in the movement was because its leadership mirrored the Black church. The Black church at the time was predominantly female membership with exclusive male leadership. Men, threatened by her authority, would undermine Ella and shun her from recognition. The SCLC pastors, including MLK, refused to allow her to share in their prestige.

Relationship with Martin Luther King

Martin (Luther King) wasnt the kind of person you could engage in dialogue with, certainly, if the dialogue questioned the almost exclusive rightness of his position.

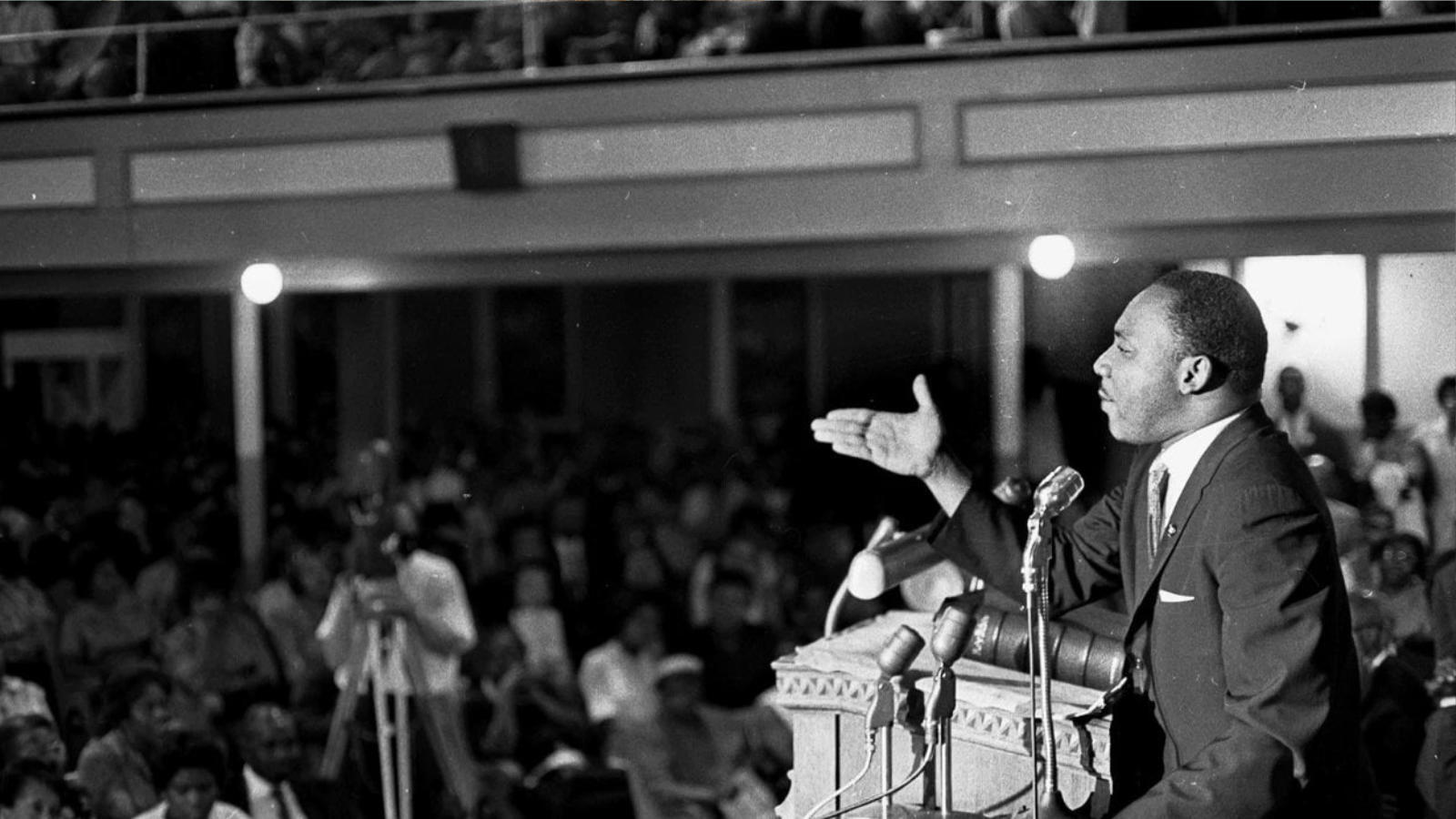

Ella Baker was critical of MLK’s charismatic, top-down leadership. Despite Ella’s experience and ability, MLK refused to have a woman’s decision out-play his own and would push Ella to the margins. As a result, their relationship was often full of tension.

In a speech she gave at the Southwide Youth Leadership Conference in 1960, Ella urged the young people to take control of the movement themselves. Ella warned them against leaders with heavy feet of clay, who would only slow down their efforts. It’s been widely accepted this was a direct challenge to MLK and his celebrity leadership style.

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee

Ella felt that the men like Martin Luther King Jr. wanted all the glory. And she was going to be working behind the scenes, and she wanted her just deserts but they werent about to give it to her, and so she decided that she couldnt take it.

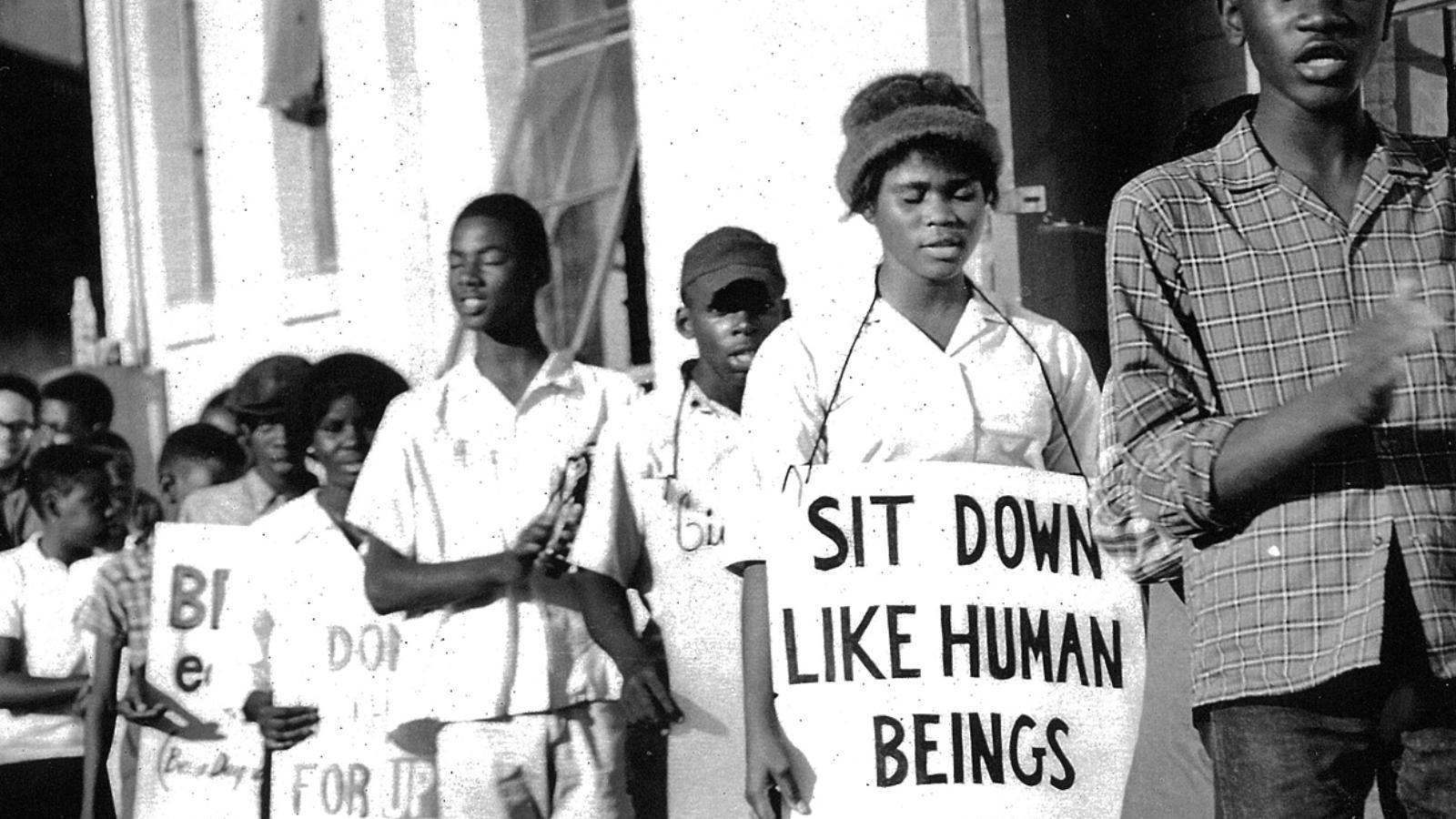

Frustrated as director of MLK’s SCLC, Ella was about to resign. At that moment, a group of college students refused to leave a Woolworth lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina. This sparked new energy in Ella, and she wrote a letter to all student leaders from the South to attend a Southwide Youth Leadership Conference.

The conference brought hundreds of young activists together to learn from each other and plan action. They were not being recognised by the movement. The middle-class and middle-aged pastor leaders were unwilling to share their platform with the young. Ella believed with some training, these brave leaders could take control and revitalise the black freedom movement.

At this conference, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) was formed (snick). Ella resigned from the SCLC and began working with the SNCC, who affectionately called her Godmother. SNCC would go on to lead the 1961 Freedom Rides, black voter registration, and draw national attention in 1964 when white supremacists murdered three SNCC workers.

Leader-less and leader-full

You didnt see me on television, you didnt see news stories about me. The kind of role that I tried to play was to pick up pieces or put together pieces out of which I hoped organisation might come. My theory is, strong people dont need strong leaders.

Ella was a woman with strong ideas about leadership. She chose to work alongside people rather than putting them in the shadow of her spotlight. Ella spoke actively against top-down authority and believed the strength of an organisation grew from the bottom up. Ella thought leadership should be collective: a movement must be leader-less and leader-full in the same breath.

Teaching the craft of organising

Oppressed people, whatever their level of formal education, have the ability to understand and interpret the world around them, to see the world for what it is, and move to transform it.

Ella’s influence was reflected in her nickname, Fundi: a Swahili word meaning a person who teaches a craft to the next generation. She spent most of her life performing the essential and challenging work of listening and building real and lasting relationships with people. She slept in their homes, spoke in their churches and earned their trust. Her way with people was how she could build movements like nobody else. People trusted and respected her because she loved them and believed in their potential.

Legacy

Ella Baker was one of the most influential leaders of the twentieth century. A woman in a fiercely sexist era, Ella made a place for herself in predominantly male political circles. Not only did she lead in those circles, but she also brought vibrant groups of women, students and activists along with her. Recognition is not only in statues, national holidays and bank notes; it’s the millions of people showing up to make a change because of your teaching. We will continue showing up for you, Ella Baker.